By Warren Cornwall. Originally published in and (c) Anthropocene Magazine, October 2022

Wildland firefighter during a prescribed burn at Sideling Hill Creek Preserve, Allegany Co., Maryland. Photo © The Nature Conservancy.

People hiking through tick-infested forests probably know the drill for avoiding tick bites, and the diseases that can come with them: Wear insect repellent and long pants. Don’t wander off trails and into dense vegetation. Check yourself afterwards for pesky hitchhikers.

Here’s another one that doesn’t find its way onto most lists: Set fire to the forest.

While not advisable for the average civilian, this strategy could make forests in the eastern U.S. less tick-friendly, according to new research.

“We believe there’s an opportunity to reduce the number of ticks by using prescribed fire to restore the health of forest ecosystems,” said Michael Gallagher, an ecologist with a U.S. Forest Service research lab in New Jersey.

Pinhead-sized parasites might seem to have a remote connection to landscape-changing forest fires. But tick-borne diseases such as Lyme Disease add up to a major and growing health problem. As many as 60,000 cases are reported in a year in the U.S. Such planet-changing forces as global warming are thought to be contributing to the problem, as rising temperatures make more places hospitable for ticks.

But less attention has been paid to the role changing forests might be playing, argue Gallagher and five other scientists hailing from the Forest Service, Pennsylvania State University, and New Jersey’s Department of Environmental Protection. So they scoured the scientific literature to understand the links between ticks and fires.

When Europeans arrived in North America, eastern forests tended to be spacious, airy landscapes filled with widely spaced pine, oak and chestnut trees. Frequent low-intensity fires set by lightning and indigenous peoples burned off fallen leaves, debris and underbrush.

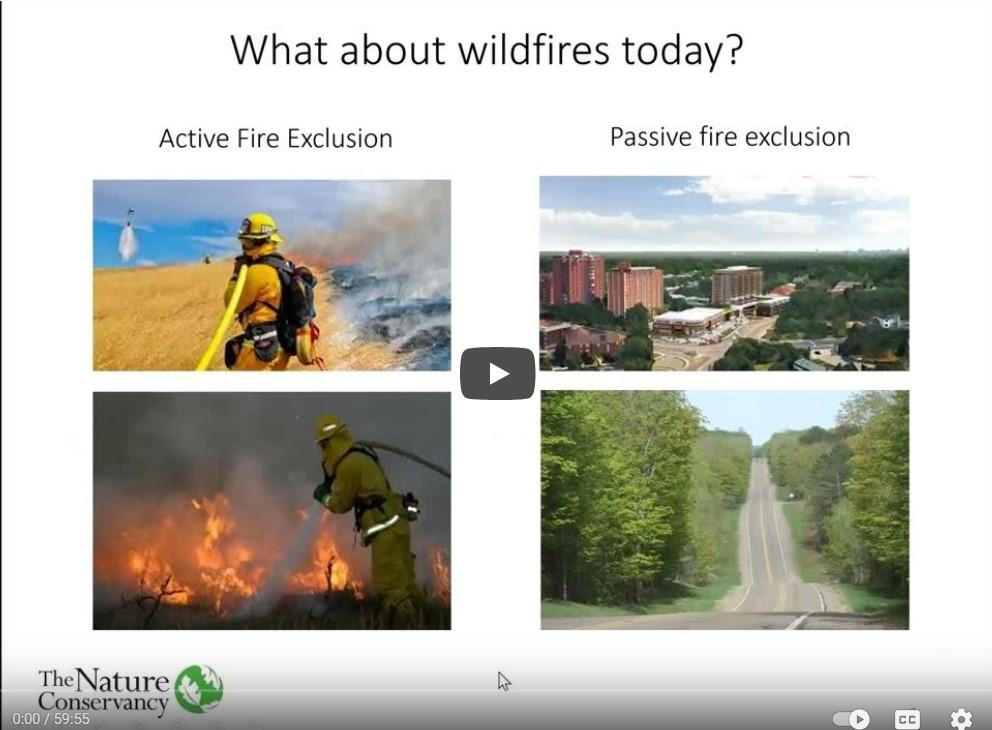

Want to learn more about fire in Maryland?

Watch our June 2022 Woodland & Wildlife Wednesday webinar,

“Fire History & Ecology in MD” on YouTube.

Such a landscape could pose problems for ticks, who thrive in moist environments with moderate temperatures and lots of underbrush, which they can climb to latch onto passing victims. These forests of old were drier and less overgrown and would have been hotter in the summer and colder in the winter when there was less vegetation to act as insulation, the scientists reported in a recent edition of Ecological Applications.

Tick numbers might have fallen at first as Europeans pushed indigenous inhabitants out of eastern forests. That’s because many of the forests were felled for timber and fuel. But starting in the 20th century, two things happened that would reverse this trend. Eastern forests began to regrow as people left their farms for cities and switched from wood to other fuels such as coal. And land management agencies such as the U.S. Forest Service adopted a policy of extinguishing all wildfires.

Those changes helped created forests that have more built-up detritus, more bushes, and more dense tree canopies. Scientists have a fancy word for this: mesophication. For the purposes of the new research, a better term might be “tick heaven.”

Fire could help reverse this phenomenon, Gallagher and his colleagues argue. They point to past studies, such as an experiment in Georgia and Florida that showed tick numbers fell in parts of a forest that were burned.

At the same time, prescribed fires bring other benefits, including creating more habitat for some species, promoting more wildflowers and grasses, removing fuel for catastrophic wildfires and making forests more resistant to insect outbreaks.

Today, land managers intentionally set ablaze just a tiny fraction of the more than 700,000 square kilometers of eastern forests. In the southeast, they burn around 28,000 square kilometers per year. The northeast, by comparison, is a slacker, at just 1,300 square kilometers.

So don’t switch your pants for shorts quite yet.

Branching Out, Vol. 30, no. 4 (Fall 2022)

Branching Out is the free, quarterly newsletter of the Woodland Stewardship Education program. For more than 25 years, Branching Out has kept Maryland woodland owners and managers informed about ways to develop and enhance their natural areas, how to identify and control invasive plants and insects, and about news and regional online and in-person events.