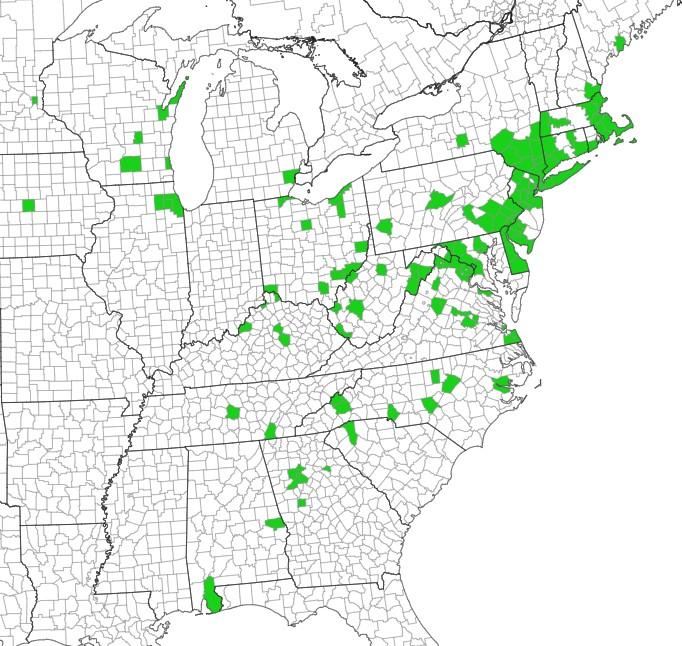

Porcelain-berry is an invasive plant reported in widely scattered area in the United States (see map below). But like many other invasive plants that were once cultivated intentionally, chances are that its impact is more wide-ranging than what the map represents. As more observers become familiar with this member of the grape family and understand the differences between it and native species, it is likely that more counties on the map will turn green, and more attention will be paid to its presence.

Those who have discovered it in areas they manage have discovered that once established, this plant can be very difficult to eradicate. The horticultural staff at Lewis Ginter Botanical Garden in Richmond, VA declare that it is “the most pervasive of all invasive plants that we are currently battling” on their grounds.

What is it?

Porcelain-berry, Ampelopsis glandulosa var. brevipedunculata, is a deciduous, climbing, woody vine also styled as “porcelain berry” or “porcelainberry.” It was introduced from northeast Asia in the 1870s as a bedding and landscape plant. It became popular for its tolerance of adverse conditions and its ability to provide ground cover. However, it is an aggressive plant that invades damp, shady areas such as streambanks, forest edges, pond margins, and disturbed areas. It forms dense mats that crowds out native vegetation, making it difficult to discover what, if anything, grows beneath it by shading them out. It can also climb into trees, reaching up to 20 feet in height.

How does it spread?

Porcelain-berry spreads both vegetatively and by animals. Birds and small mammals eat the fruit and spread the seeds through their droppings. The seeds sprout readily and may be viable in the soil for several years. The plant also reproduces asexually by re-sprouting from its roots.

How can I identify it?

The vine has deciduous, heart-shaped leaves that have coarse teeth along the margins. Because porcelain-berry’s stems may closely resemble native grapes superficially, it is important to recognize a few important distinctions that can assist in identification. For example, the bark of native grapes shreds or peels; porcelain-berry’s does not. Additionally, the center of a native grape’s stem is brown; porcelain-berry’s is white. In June through August, the vine develops groups of white flowers which in September and October turn into berries of a variety of colors. Beginning as white fruits, they turn yellow, lilac, green, or turquoise. Observing both the small flowers and the fruits will also aid in identification. Native grape flowers and fruits droop from the vine. Porcelain-berry flowers and fruits are held above the stem, even when the stem is drooping.

See the photo gallery below.

How can I control it?

Porcelain-berry can be controlled by a variety of methods. As with most invasive plants, the best time to control it is during early detection. Repeated treatment will likely be necessary after initial removal because seeds may remain viable in the soil or because unseen root fragments may exist from which new growth will occur. Hand-pulling vines in the fall or early spring will prevent flower buds from producing the following season. If the plants are already producing fruit, take care to ensure that all fruit is collected when the stems are being removed to prevent seed dispersal. Larger vines can be removed with shovels, but care must be taken to ensure that the entire root system is removed to prevent re-sprouting.

Chemical treatment may be necessary to supplement manual or mechanical methods if the infestation is sufficiently large. Cut large vines during the summer and allow to re-sprout before treating with glyphosate. Foliar and basal-bark applications with triclopyr-based formulations are also effective.

For more information:

Learn more about porcelain-berry:

Fact Sheet: Porcelain-berry (Plant Conservation Alliance)

Unwanted and Un-loved: Porcelain-berry! (Virginia Native Plant Society)

Ampelopsis brevipedunculata (North Carolina Extension)

English

English العربية

العربية Български

Български 简体中文

简体中文 繁體中文

繁體中文 Hrvatski

Hrvatski Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Nederlands

Nederlands Suomi

Suomi Français

Français Deutsch

Deutsch Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά हिन्दी

हिन्दी Italiano

Italiano 日本語

日本語 한국어

한국어 Norsk bokmål

Norsk bokmål Polski

Polski Português

Português Română

Română Русский

Русский Español

Español Svenska

Svenska Català

Català Filipino

Filipino עִבְרִית

עִבְרִית Bahasa Indonesia

Bahasa Indonesia Latviešu valoda

Latviešu valoda Lietuvių kalba

Lietuvių kalba Српски језик

Српски језик Slovenčina

Slovenčina Slovenščina

Slovenščina Українська

Українська Tiếng Việt

Tiếng Việt Shqip

Shqip Eesti

Eesti Galego

Galego Magyar

Magyar Maltese

Maltese ไทย

ไทย Türkçe

Türkçe فارسی

فارسی Afrikaans

Afrikaans Bahasa Melayu

Bahasa Melayu Kiswahili

Kiswahili Gaeilge

Gaeilge Cymraeg

Cymraeg Беларуская мова

Беларуская мова Íslenska

Íslenska Македонски јазик

Македонски јазик יידיש

יידיש Հայերեն

Հայերեն Azərbaycan dili

Azərbaycan dili Euskara

Euskara ქართული

ქართული Kreyol ayisyen

Kreyol ayisyen اردو

اردو বাংলা

বাংলা Bosanski

Bosanski Cebuano

Cebuano Esperanto

Esperanto ગુજરાતી

ગુજરાતી Harshen Hausa

Harshen Hausa Hmong

Hmong Igbo

Igbo Basa Jawa

Basa Jawa ಕನ್ನಡ

ಕನ್ನಡ ភាសាខ្មែរ

ភាសាខ្មែរ ພາສາລາວ

ພາສາລາວ Latin

Latin Te Reo Māori

Te Reo Māori मराठी

मराठी Монгол

Монгол नेपाली

नेपाली ਪੰਜਾਬੀ

ਪੰਜਾਬੀ Afsoomaali

Afsoomaali தமிழ்

தமிழ் తెలుగు

తెలుగు Yorùbá

Yorùbá Zulu

Zulu ဗမာစာ

ဗမာစာ Chichewa

Chichewa Қазақ тілі

Қазақ тілі Malagasy

Malagasy മലയാളം

മലയാളം සිංහල

සිංහල Sesotho

Sesotho Basa Sunda

Basa Sunda Тоҷикӣ

Тоҷикӣ O‘zbekcha

O‘zbekcha አማርኛ

አማርኛ Corsu

Corsu Ōlelo Hawaiʻi

Ōlelo Hawaiʻi كوردی

كوردی Кыргызча

Кыргызча Lëtzebuergesch

Lëtzebuergesch پښتو

پښتو Samoan

Samoan Gàidhlig

Gàidhlig Shona

Shona سنڌي

سنڌي Frysk

Frysk isiXhosa

isiXhosa