What are cultivars of native plants?

We add native plants to our yards to attract and support pollinators as they pass through. Many native bees, and all moths and butterflies, need native plants to complete their life cycles. The decline of insect populations has numerous causes, but is directly tied to the decline of natural areas with thriving native plant populations. On this webpage we examine how the native plants in our landscapes affect the health of wild native plant populations.

Hereditary material (DNA in the genes of plant pollen and seeds, for example) moves from our yards into natural areas. Pollinators and wind transport pollen over distances ranging from less than a mile to many miles. The wind also transports many types of seed, while others are carried by animals. Seeds carried by birds can travel many miles between consumption and deposition. A yard does not need to be adjacent to a natural area to share DNA with it.

How do you suppose altering the height, leaf color, vigor, or compactness of the hypothetical native plant species shown might change the way it interacts with the other species in its habitat?

When the native plants in our yards are locally-sourced and locally-adapted, their DNA can make a positive contribution to the survival of wild plant populations. The adaptive genetic diversity they share is important because it allows native species to persist despite the rapidly changing conditions of our modern environment.

When the plants in our yards are cultivars of native species, their genetic makeup is the result of artificial rather than natural selection and they possess little genetic diversity. The offspring of cultivars crossed with native plants are called hybrids. Many vegetable gardeners are familiar with the consequences of hybridization. Sweet peppers cross-pollinate with hot peppers in the same garden. The hybrid seeds that result produce peppers with variable levels of heat. Similarly, sweet corn cross-pollinates with field corn. The ears that result contain kernels expressing the range of flavor and texture of their parents, not being ideal for either purpose. In the vegetable garden, we can easily dispose of unwanted hybrids. Once the DNA from cultivars of native plants makes it into wild populations, there is no way to dispose of it. The new DNA affects the ability of wild native plants to survive and has ramifications for all the species that interact with the native plant as well. Studies have shown that, in some cases, cross-pollination with cultivated varieties resulted in the loss of the wild relative.

Nativar is a word resulting from the combination of the words native and cultivar. It has the good quality of being shorter than “cultivar of a native plant”. However, the inclusion of the entire sound of the word “native” lends the impression that they are good ecological substitutes for native plants. Although they are marketed regionally as native plants, they are sold throughout the world.

The products we consider nativars are sold all around the world, as demonstrated by this webpage selling our native foxglove beardtongue. Enter the name of a cultivar of a native plant and a few words in a foreign language into your search engine and see how many places you can find it for sale.

Common misperceptions about cultivars of native plants

Misperception #1: It’s always bad to use cultivars of native plants.

Facts to Consider: The question is not whether it’s morally wrong to use cultivars, but whether they are good for ecosystem health. Sterile cultivars of native plants are benign, they can’t cross-pollinate with their wild relatives, so they pose no risk to wild plant populations. When cultivars are beneficial to ecosystems, they are good. For example, plant breeders are working to create disease-resistant cultivars of native tree species that have been hit hard by non-native invasive plant pathogens. If done with care, it is possible that such cultivars could be used to intentionally spread beneficial DNA into wild plant populations and help restore those species.

American chestnut provides an example of cultivar development that is sensitive to, and in fact geared towards, the benefit native plants and natural areas. The cultivar is resistant to the invasive plant pathogen chestnut blight, and is being tested for interactions with other species in its habitat. The cultivar will be deployed in a way that will insert the beneficial DNA into wild populations while preserving local adaptive genetic diversity. Image credit: by Daderot via Wikimedia Commons.

When cultivars are harmful to ecosystems, we must ask whether the benefit to people outweighs the risk to native plant species and pollinator populations. Cultivars of plants aren’t just bred for ornamental use, but for food and medicinal value as well. For example, the genes of our native strawberry are present in many commercial strawberry cultivars.

Misperception #2: The number of plants we put in our yards is insignificant compared to the number found in natural areas.

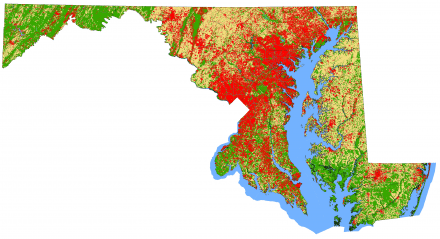

Facts to Consider: Actually, cultivars do not need to outnumber their wild relatives in order to have a profound impact on their DNA. Even so, in Maryland, the combined acreage of commercial/residential (red), and agricultural land (tan) is greater than the acreage of remaining natural areas (green). For many native species, the number of cultivated plants grown in residential and commercial areas may exceed the number of wild ones growing in the green areas. For example, Maryland’s green industry sells tens of thousands of butterfly weeds annually. In Maryland, the number of potted butterfly weeds sold in a single year probably outnumbers the total number of butterfly weeds growing in the wild.

Green = natural areas, tan = agricultural fields, red = urban and suburban developed areas. Base map: 2030 Land Use Map, Maryland Department of Planning.

Misperception #3: Nativars used in urban areas can’t contaminate native plant populations in natural areas.

Facts to Consider: Some pollinators travel long distances, with migratory pollinators being extreme examples of this. Some plants are wind-pollinated, and their pollen is carried for miles. Barriers like parking lots and highways do not discourage wind-borne pollen. Seeds carried by wind, water, or birds travel long distances. Seeds from our yards wash down storm drains into local stream parks. Once the seed of a cultivar establishes in a wild population, gene flow accelerates. The literature offers many examples of wild plants that have been genetically replaced by their domesticated relatives.

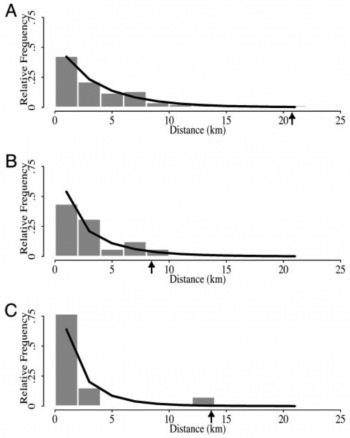

The graph above is from a study of cultivars of creeping bentgrass. Pollen from the cultivars traveled up to 20 km, as shown on the x-axis, and fertilized

A) other planted cultivars of the same species,

B) wild relatives of the same species, and

C) wild relatives of a different species in the same genus.

The fraction of offspring containing DNA from cultivar pollen is as high as three quarters, as shown on the y-axis. A. From Watrud et al. 2004.

Misperception #4: Adding the gene types of cultivars into natural areas is good because it increases the genetic diversity of the system.

Facts to Consider: It is true that the simple definition of genetic diversity is the sum of all the different types. However, some types of genetic diversity are bad for local ecosystems. Plant populations and natural areas benefit from adaptive genetic diversity, not random genetic diversity. Switchgrass cultivars provide two good examples.

1. Seed dormancy has been bred out of several native grass species to create cultivars for use where quick establishment from seed is desirable. Seed dormancy, however, is an attribute that prevents native seeds from germinating before winter is over. The addition of this genetic diversity would be harmful to wild switchgrass populations.

2. It is true that cross-pollination with strong cultivars can make wild relatives stronger. In natural areas, this could benefit the plant species as well as the pollinators and songbirds that depend upon it. However, increased vigor would also make the wild relatives more effective at competing with other plant species. The switchgrass cultivar, ‘Shelter’, provides a good example. It has been bred for increased vigor, and it establishes quickly and takes over an area completely. Other meadow grasses and flowers, and all the insects and birds that depend upon them lose out. The balance of the ecosystem is at risk.

Our native swamp rose mallow has green foliage and white or pink flowers. Artificial selection has produced cultivars, like those shown here, with red foliage and red flowers. One reason we plant natives in our yards is to support pollinators by providing pollen and nectar. The other is to support an abundance and diversity of insects by providing host plant tissue. Recent studies (Tenczar and Krischik 2007; Baisden and Tallamy 2018) show that cultivars with reddened foliage are vastly inferior to host plants.

The rose mallow flowers in the wild population (above) were once pink and white, the natural colors for their species. Now many of the flowers are red, colors inherited from cultivars planted in a nearby subdivision. The foliage (below) is also reddish, another sign of hybridization with cultivars. Although beautiful to the human eye, the consequences for rose mallow as a species and the animal that depend upon it have not been studied. Several moth and butterfly species use swamp rose mallow as a host plant; many bees collect nectar and pollen, including one specialist bee; and the ruby-throated hummingbird is a frequent visitor.

Misperception #5: The most important performance yardstick is how often pollinators visit cultivars of native plants in garden trials.

Facts to Consider: Pollinators need their native plants in natural areas. If a cultivar attracts lots of pollinators in the garden but disrupts the balance of natural systems, then, taking the larger view, it has not benefited pollinators. No Mid-Atlantic native plant cultivar has been tested to determine the impact of cross-pollination on wild populations or their pollinators.

Misperception #6: Cultivars of naturally occurring sports are not a concern.

Facts to Consider: Sports are sometimes the result of recessive genes expressed as a result of inbreeding, in other words, they lack the quantity of adaptive genetic diversity present in most wild plants. Other times, they are the result of random mutations and usually are not adaptive, although the naturally occurring parent of Cornus florida ‘Appalachian Spring’ provides an exception to that rule. In any case, the problems of mass production of a small number of individuals remain.

Misperception #7: Local ecotype native plants are no good because of climate change.

Facts to consider: Climate change models based on a scenario where we begin to change our emissions behavior now show that Maryland's climate will be like Virginia's in the year 2100, and the impact on native plants won't be severe.

How to support local ecosystems and still enjoy your yard

1. Gradually remove invasive species from your landscaping.

2. Support your local park’s efforts to remove invasive species.

3. Figure out which wild-type native plants you like enough to plant in your yard. Start with our Recommended Native Plants for Maryland for ideas. Ask your garden center for locally adapted, genetically diverse plants.

4. Enjoy an assortment of non-invasive, non-native species. They come in every shape, height, and color. Examples include lilac, crepe myrtle, and many roses. Sterile alien cultivars are particularly safe for local ecosystems. Examples include German bearded irises and 'Karl Forster' grasses. Plant breeders are currently working on sterile cultivars of many old landscaping favorites that turned out to be invasive, so there is much to look forward to in this regard.

5. Enjoy cultivars of native plant species that are sterile. These cannot cross-pollinate with their wild relatives. For example, many of the modern hydrangea cultivars are descendants of our native wild hydrangea (Hydrangea arborescens). Sterile cultivars may lack the pollen, nectar, and/or seed benefits to wildlife, but still have host plant value for native insects. In any event, the main purpose is to buy a plant you enjoy that does not hurt natural areas.

6. Soon you may have the option to purchase native plant cultivars that were developed for the purpose of benefiting native plants and their habitats. It seems likely that American chestnut cultivars will hit the market within a few years.

Additional resources

Ellstrand, Norman. Dangerous Liaisons: When Domesticated Plants Cross-Pollinate with their wild relatives. 2003. Johns Hopkins University Press. 264 pp.

Baisden, Emily C., Douglas W. Tallamy, Desirée L. Narango, and Eileen Boyle. 2018. Do cultivars of native plants support insect herbivores? HortTechnology 28(5) 596-606.

Carignan, C. (2018, Nov. 12). The Nativar Dilemma: The Case of My Purple Ninebark & The Leaf Beetle [Maryland Grows Blog].

Maryland Native Plant Society. List of nurseries that sell native plants. www.mdflora.org

Nelson, C., et al. 2014. The forest health initiative, American chestnut (Castanea dentata) as a model for forest tree restoration. Acta Horticulturae. 1019:179-190.

Tenczar, Emily G. and Vera A. Krischik. 2007. Effects of New Cultivars of Ninebark on Feeding and Ovipositional Behavior of the Specialist Ninebark Beetle, Calligrapha spiraeae (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Hortscience 42(6):1396–1399.

Watrud, L. S., Lee, E. H., Fairbrother, A., Burdick, C., Reichman, J. R., Bollman, M., … Van de Water, P. K. 2004. Evidence for landscape-level, pollen-mediated gene flow from genetically modified creeping bentgrass with CP4 EPSPS as a marker. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(40):14533–14538.

By Dr. Sara Tangren, former Sr. Agent Associate, University of Maryland Extension, May 2019. The author appreciates input from Jon Traunfeld on the issue of cross-pollination and hybridization in vegetable varieties.

Still have a question? Contact us at Ask Extension.