FS-2022-0634 | January 2023

Stigma Pollutes Our Thinking

People can take a variety of actions to maintain or improve their mental health. However, research shows that even when faced with significant mental distress, many people still do not seek professional assistance (Newson et al., 2021). One of the most common reasons why people do not seek treatment is the preference for self-help. The roots of this preference in American culture are deep, and contribute to internalized stigma about seeking treatment for mental illness. This fact sheet will provide the background and strategies necessary to recognize unexamined, stigmatizing beliefs about mental health care. Challenging internalized stigma about mental health care can make it easier to seek professional treatment when necessary.

Self-help is just part of maintaining one’s mental health.

Diet, exercise, sleep, meditation, social engagement – all are important strategies to promote wellness and resilience (Swarbick, 2006). However, focusing only on these self-help strategies may overlook the need for professional help and can imply that everyone should always be able to pull themselves up by the bootstraps. Furthermore, the longer someone avoids seeking professional help for a mental health challenge, the more difficult treatment and recovery can be.

When facing intense, chronic stress, it is possible that multiple domains of life may be affected, including work, personal life / relationships, and day to day responsibilities. At that point, self-help strategies may be insufficient for one’s recovery. People experiencing severe impairment deserve and need the help of various types of mental health professionals to take care of themselves.

Cultural factors contribute to delays in seeking professional help.

Despite facing clear symptoms of a mental health challenge, many people delay treatment because of a preference for self-help (Newson et al., 2021). For many Americans, personal responsibility and independence are core values (Kasulis, 2002). It is difficult to spend any amount of time in independence-oriented cultures (including mainstream United States culture) without being exposed to these core values, whether one agrees without how they are applied, or not. This is not unlike passively breathing in pollution from a nearby factory, even if one does not agree with the amount of pollution the factory is allowed to emit. We learn from childhood that our country was born from a declaration of independence. Stories of “rags to riches” and “the American Dream” suggest that a better life is in reach based on self-reliance and individual hard work.

These values are deeply ingrained through years of passively breathing them in. Because it is common for identity and values to be based on social norms and not specifically on personal reflection (Crocetti et al., 2022), many people may unthinkingly label the pursuit of professional mental health care as weak or too dependent. Even when this judgment is not cast on others, it may be directed inward as internalized stigma. Individuals are often most critical of their own behavior in this respect. People often feel personally ashamed for seeing a counselor, calling a crisis line, or considering mental health medications.

Internalized stigma can have unnoticed effects on our healthcare choices.

These automatic reactions come from powerful stereotypes which keep many people away from help that would allow them to recover and resume their responsibilities. Additionally, they can make those who do seek professional help feel terrible about themselves.

This internalized stigma towards mental health, substance use problems, and professional care is harmful. It adds an extra burden to suffering, family disruption, anger and substance use, job troubles, inability to function, and suicide risk. Most importantly, it contributes to an overreliance on self-help or personal responsibility when professional help may be needed.

In conclusion, personal responsibility and individuality have their rewards. For example, children who are able to demonstrate self-regulation are more likely to show both short- and long-term social, academic, and even financial success (Cantor et al., 2019). However, children and adults experiencing prolonged stress without sufficient assistance are less able to effectively use strategies rooted in personal responsibility (Shonkoff et al., 2012). In other words, personal responsibility sets us up for success, but cannot be our only tool during difficult times. If someone is facing mental illness that has lasted weeks or longer without change, it is important to consider professional assistance. To make this choice more accessible, one may also have to confront internalized stigma. See the final page of this document for some concrete strategies to combat internalized stigma.

Self-screening is a useful resource.

Mental Health America offers an online mental health screening test. Results can provide feedback about whether professional help may be useful. Scan the QR code with a smartphone to visit the site.

Other resources

- The Pro Bono Counseling Project, based in Baltimore, connects Marylanders to licensed, volunteer therapists at no cost. Call Pro Bono Counseling at 410-825-1001 for a confidential phone interview.

- The Center for Healthy Families at UMD’s School of Public Health offers sliding scale fee individual, couples, and family counseling. https://www.thecenterforhealthyfamilies.com/

- Maryland 2-1-1 is the central connector for community resources, including mental health across the state. Simply dial 211 to reach an operator or visit https://211md.org

References

- Cantor, P., Osher, D., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2019). Malleability, plasticity, and individuality: How children learn and develop in context. Applied Developmental Science, 23(4), 307-337.

- Crocetti, E., Albarello, F., Meeus, W., & Rubini, M. (2022). Identities: A developmental social-psychological perspective. European Review of Social Psychology, https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2022.2104987

- Kasulis, T. P. (2002). Intimacy or integrity: Philosophy and cultural difference. University of Hawai‘i Press.

- Newson, J., Pastukh, V., Taylor, J., & Thiagarajan, T. (2021). Mental health has bigger challenges than stigma. Mental Health Million Project. https://sapienlabs.org/wp- content/uploads/2021/06/Rapid-Report-2021-Help-Seeking.pdf

- Shonkoff, J. P., Garner, A. S., Siegel, B. S., Dobbins, M. I., Earls, M. F., McGuinn, L., … Wood, D. L. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–e246. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2663

- Swarbrick, M. (2006). A wellness approach. Psychiatric rehabilitation journal, 29(4), 311-314.

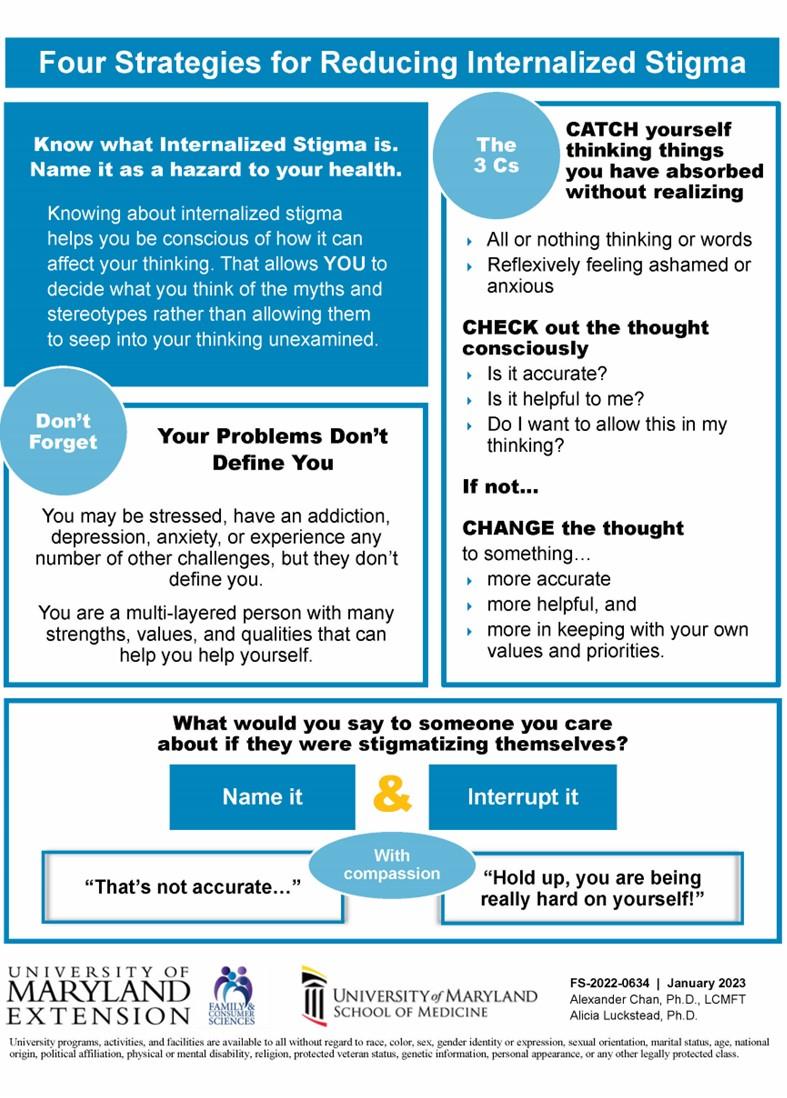

Four Strategies for Reducing Internalized Stigma

Know what Internalized Stigma is. Name it as a hazard to your health.

Knowing about internalized stigma helps you be conscious of how it can affect your thinking. That allows YOU to decide what you think of the myths and stereotypes rather than allowing them to seep into your thinking unexamined.

Don’t Forget

Your Problems Don’t Define You

You may be stressed, have an addiction, depression, anxiety, or experience any of other challenges, but they don’t define you.

You are a multi-layered person with many strengths, values, and qualities that can help you help yourself.

The 3 Cs

CATCH yourself thinking things you have absorbed without realizing

- All or nothing thinking or words

- Reflexively feeling ashamed or anxious

CHECK out the thought consciously

- Is it accurate?

- Is it helpful to me?

- Do I want to allow this in my thinking?

If not…

CHANGE the thought

to something…

- more accurate

- more helpful, and

- more in keeping with your own values and priorities.

What would you say to someone you care about if they were stigmatizing themselves?

Name it and Interrupt it

“That’s not accurate…”

With compassion

“Hold up, you are being really hard on yourself!”

ALEXANDER CHAN, PH.D., LCMFT

alexchan@umd.edu

ALICIA LUCKSTEAD, PH.D.

aluckste@som.umaryland.edu

This publication, Stigma Pollutes Our Thinking (FS-2022-0634) is a part of a collection produced by the University of Maryland Extension within the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources.

The information presented has met UME peer-review standards, including internal and external technical review. For help accessing this or any UME publication contact: itaccessibility@umd.edu

For more information on this and other topics, visit the University of Maryland Extension website at extension.umd.edu

University programs, activities, and facilities are available to all without regard to race, color, sex, gender identity or expression, sexual orientation, marital status, age, national origin, political affiliation, physical or mental disability, religion, protected veteran status, genetic information, personal appearance, or any other legally protected class.