Grafted Watermelon Spacing Study

Introduction

Fusarium wilt in Watermelons is caused by the soil borne pathogen Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Niveum and several new races have been identified in Maryland. There are few options for fungicide products to treat fields with this disease. Therefore, once a field has become infected with an outbreak of fusarium future watermelon production is not economically feasible. However, research has shown that grafted seedless watermelons can be grown successfully in areas with previous fusarium wilt infection.

University of Maryland Extension has conducted research trials of the past several years analyzing the yields and fruit quality of grafted watermelons on farms with a history of fusarium using two different rootstocks and found that Carolina Stongback, a citron interspecific hybrid, has performed well under fusarium pressure as well as root knot nematode pressure.

One reason growers might hesitate to use grafted plants over traditional seedless watermelons is because they cost more. However, it has been noted by other research that grafted seedless plants are more vigorous than ungrafted seedless plants. This year, the goals of this study were to understand plant spacing’s effect on yield of graphed watermelons where the scion was a seedless melon variety, Fascination, and the rootstock was Carolina Strongback. This study was planted on two farms, one the Eastern Shore of Maryland in Wicomico County, and the second was planted on the Western Shore in St. Mary’s County. Results from the Wicomico County experiment have been collected and analyzed and are discussed below.

Methods

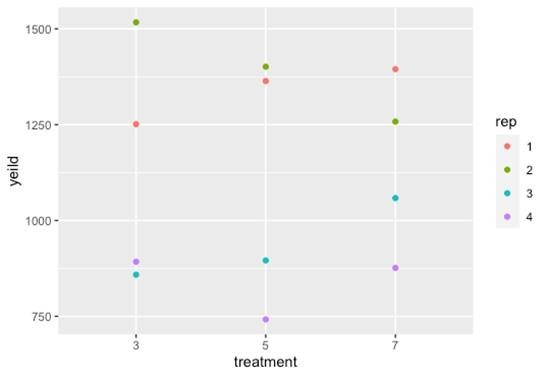

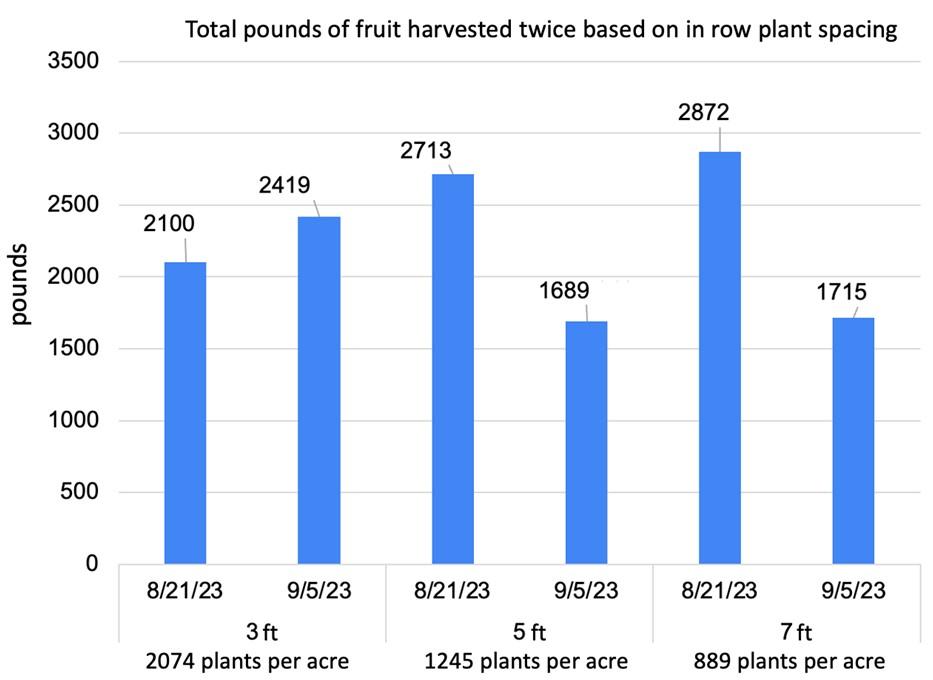

At the Wicomico County site transplants were planted in plastic on June 9th. Rows were spaced at 7 ft between centers. The plant spacing treatments within rows were 3 ft, 5 ft and 7 ft, for population per acre sizes of 2074, 1245, 889 plants per acre respectively. The experiment stretched across 6 rows, and each treatment rep was 61 ft long. Pollinator plants were also on grafted on Carolina Stongback rootstocks and were spaced every third seedless plant throughout the field. Fruit was harvested from each plot in a 20 ft area across the 6 rows (image 1). Two harvests were performed on August 23rd and September 7th. Fruit weight and the number of fruits harvested from each plot was recorded for yield analysis (image 2).

Results

Yields for the four replicates were inconsistent (fig 1) because of an outbreak of Phytophthora which the grafted plants have no additional resistance to. There were no significant differences between the yields of the 3,5,7 ft spacing groups, although the overall yields were higher in the 7, and 5 ft spacing treatments. However, there were more melons harvested from the 7, and 5 ft spacing group in the first harvest on August 23, whereas there were more melons harvested from the 3 ft spacing treatment in the second harvest (fig x). There were differences in the weight of individual melons between the three treatments. Melons harvested from the 5 and 7 ft spacing plots were significantly heavier than melons harvested from the 3 ft spacing treatments.

Conclusions

Based on our results at the Wicomico farm location there was no yield penalty associated with a lower plant density spacing. Additionally, melons from the 7 and 5 ft spacing treatments came in earlier, or had a higher proportion of ripe fruit at the first picking compared to the 3 ft spacing treatment which had more harvestable fruit during the second picking. Based on these results from the Wicomico farm and previous year’s results, farmers can offset some of the higher cost of grafted watermelons by purchasing fewer plants than they would need in a regular seedless melon field.